Waverley Mills

Guy DempsterHow our visit to one of the oldest (and only) textile mills in the country got me thinking about the future of circular milling in Australia.

Otis and I are in the middle of a two week trip to Türkiye and Spain, visiting various milling and knitting tech companies as we hunt for machinery for our Tassie micro mill. Over the past few months since winning eBay’s Circular Fashion Fund Award I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the ideal shape our operation might take, and what approach would make the most sense in Australia.

In pursuit of answers and insight, Otis and I flew to Launceston in late March for a brief but invaluable field trip to Waverley Mills.

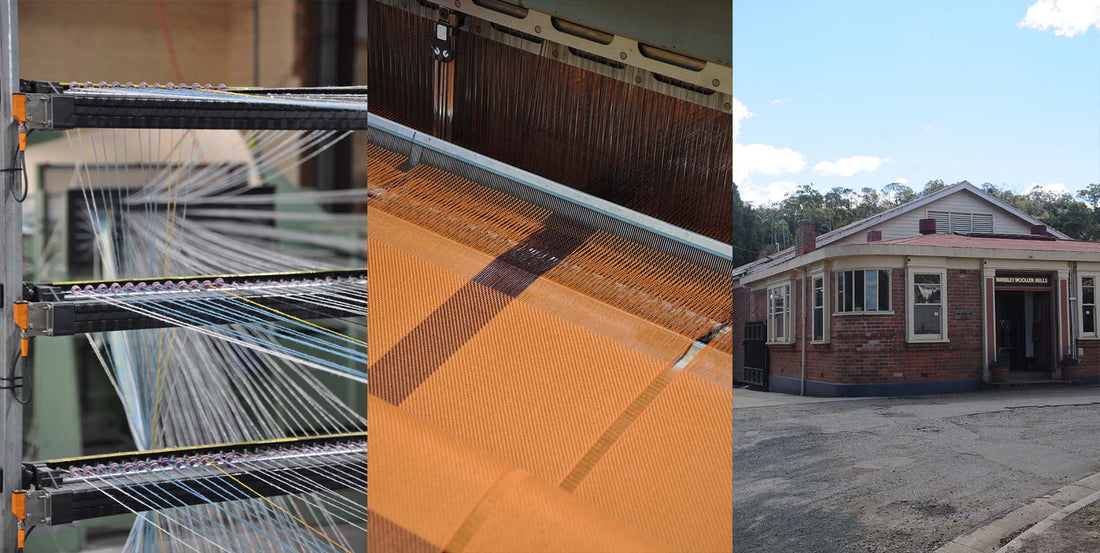

Established in 1874, Waverley specialises in spinning, dyeing and weaving their signature range of blankets, in addition to various woven textile projects commissioned by industry– most recently including their new contract with The Spirit of Tasmania, and projects with fashion labels Nudie Jeans, Country Road and RM Williams.

MILL TOUR

We were given a fantastically comprehensive tour of the mill by managing director Dave Giles-Kaye and COO Jesse Ciezki. This began with their fibre processing and yarn spinning facility, through to their dyeing, warp preparation, weaving and finishing stations. It was astounding to see such extensive capabilities all housed under the one roof– operated by a dedicated team of practitioners flexing expertise you’re unlikely to find anywhere else in Australia.

My background is in knitwear and knitted textiles, so I’d never before seen a woven production line like this. Getting up close to inspect Waverley’s electronic looms was a particular highlight.I’ve often wondered how the complicated ‘throwing’ of the shuttle required on a hand loom was replicated by an automated machine.

On Waverley’s looms the process required two mechanical shuttle feeders– one that shot out from the left, pulling the weft thread halfway across, where it was collected by a feeder from the right which hooked the yarn and pulled it the rest of the way across. Very much like the two arms of a human reaching around and retrieving.

The loom technician slowed the machine right down to demonstrate this, before flicking it back up to full speed, the shuttle feeders then moving so fast they were an invisible blur.

Another highlight included the bouclé yarn spinning machine, which would sandwich wool fibre between a spun woollen yarn and fine, nylon thread to create this distinctive, highly textural textile.

However one of Waverley’s most interesting features– at least to me– was their massive fibre recovery machine.

The machine is several decades old, but was recently refurbished by the mill’s head engineer, who installed a component on the very end which filters the output to ensure finer, more evenly detangled fibres.

Seeing this machine and getting to trade notes on the practice of fibre recovery with the Waverley team was super encouraging. The endless variability of the process was a shared challenge: the type of waste you’re recycling, how its prepared, the particularities of the fibre recovery machinery, the blending and spinning equipment used and how each of these steps will affect the final product and its usability.

It's quite the production puzzle.

Otis and I left feeling inspired, and over the interim months I’ve been thinking a lot about how textile milling could evolve in modern Australia. Over the last 150 years Waverley Mills has expanded, shrunk, gone into hibernation and been resurrected several times. It’s held on while countless other players have vanished entirely, the mass offshoring of manufacturing quashing any incentive to invest in local capabilities.

My hope, however, is that we’re on the edge of change. Waverley’s newest reinvigoration cost $16.5 million; a combination of private and public investment to expand this bastion of expertise into a well-equipped, modern, circular mill, with an especial focus on resource recovery and reuse.

THE IDEAL SCALE

One argument as to why more manufacturing isn’t done in Australia is that our population and thus domestic consumer base is too small to support Economies of Scale (EoS) production, and that even if we wanted to competitively export what we make, we’ve fallen too far behind the rest of the world in manufacturing capabilities to ever justify the cost to reequip ourselves, catch up and compete.

The logic goes that in order to make things cheaply enough to suit the modern customer (after adding enough of a profit margin to make your business attractive to investors), you need to reach a critical mass of production volume.

As the volume of production goes up, the price per unit goes down. It’s a whole lot of math to do with consolidation and streamlining processes, increased efficiency and bulk discounting of supplies and logistics services.

This formula can be very advantageous if you’re producing consumables our society crucially needs in huge, continuous volumes– like food or medicine. However when applied to discretionary items like fashion or textile products, I’m increasingly sceptical that we’ll ever find a ‘healthy’ approach to mass production.

The very nature of the beast is that you are producing to achieve optimal economic efficiency, rather than to meet the needs of a population where they naturally sit. To sell all this unnecessary stuff, the fashion industry and the greater culture goes to enormous, expensive lengths to foster demand for all this product– often through massive marketing campaigns convincing us that we need something because of its invented cultural merit.

Now I’m an aesthete and a fashion kid at heart, and I never want to discount the vital importance of beauty, variety and craftsmanship to a culture. I’m not proposing a cult of sartorial totalitarianism where we all wear matching beige potato sacks because anything else would be a ‘discretionary’ extravagance.

My problem with the ‘bigger is better’ Economies of Scale approach is that it absolutely guarantees waste. It is overproduction.

And although the upfront cost to the consumer may be cheap, the cost worn by our communities and our environment as we struggle to contend with all this waste is enormous, perpetually unaccounted for and only getting dearer. In economics, these unmeasured costs and consequences are called ‘negative externalities’.

This is precisely why the federal government’s Seamless Clothing Stewardship Scheme is so radically necessary– it seeks to shift the responsibility to remedy these negative externalities on to the megabrands that profit the most from this lopsided approach, and off the taxpayer and charity sector, who currently flip the bill.

Earlier this year France took this approach a step further, moving to regulate the worst, ‘ultra-fast fashion’ offenders, in the hopes of curbing waste and giving the local manufacturing sector a fighting chance.

However it does make you think: if companies engaging in massive EoS manufacturing were forced to pay for the environmental impact of their overproduction and the development of services to maintain, repair, recover and recycle their products, wouldn’t that make their entire business model far less ‘economical’? Production and operational costs would shoot up and perhaps even cancel out the EoS savings, profit margins would have to shrink to keep the product enticingly cheap (unless you’ve achieved market monopoly and can corner the customer into paying whatever you want *cough* Woolies), and shareholders everywhere would despair!

Admittedly this is a rather reductive, un-nuanced assumption about a very complicated system, but I’d still argue such a correction is necessary to improve the outlook for the health of our planet.

If that’s considered ‘uneconomical’ then maybe we need to rethink Economics.

Concurrently it does make me wonder whether there is an approach to domestic textile milling that would make healthier, better sense in Australia, deliberately designed to cater to our ‘smaller’ population (I mean, 26 million sounds like plenty to me but whatever), refining demand rather than inventing it, and actually takes responsibility for the environmental footprint of the production process (Waverley being one of the few players actively pushing towards this frontier).

There’s plenty of space to argue for more automated, integrated technological solutions to bolster this kind of lean, green, hyperlocal approach, but in my mind that’s only half the battle.

If there’s anything I’ve learned from the recent bankruptcy of Swedish textile recycling startup Renewcell, it’s that you can have all the investment and viable tech capabilities a newcomer could dream of, but if the greater industry isn’t willing to take the leap with you and endure even the slightest disruption to business as usual… good luck, sis.

SHARING IS CARING

Thankfully, there’s a whole new philosophy for recycling and manufacturing evolving right under our noses, advocating for much more than just newfangled tech solutions.

One proponent of this new wave, whose approach and ethos I love, is One Army.

This is a global network of environmentalists and problem-solvers founded by Dutch designer Dave Hakkens. It began in 2013 with a project Hakkens completed for his MA at the Design Academy of Eindhoven, Netherlands, for which he built a mini-scale plastics recycling machine line.

This consisted of a shredding machine which cut rigid plastics down into confetti-sized shards, a melting machine which turned these shards into a thick, viscous liquid, and finally compression, extrusion and injection machines which would mould this liquid plastic into new shapes and products.

Photo Credit: Precious Plastic

Photo Credit: Precious Plastic

This is standard practice for plastic recycling, but with a crucial twist: each piece of equipment was built with cheap, easy-to-source materials and components, and with them Hakkens published open-source, detailed schematics for how anyone, anywhere could construct these machines themselves.

The project kickstarted what is now called the Precious Plastic movement. Over the past decade, as Hakkens refined the machine designs, broadcast his approach and expanded his network of collaborators, people all over the world came to rely on his plans and library of instructional Youtube videos to develop their own in-house plastic recycling capabilities.

There are now over a thousand organisations around the world operating self-built plastic recycling machinery following this approach, servicing their local communities by recycling plastic waste and showcasing circularity best practice.

In Australia these include Precious Plastic Victoria in Melbourne and Defy Design in Sydney– who Otis and I visited when they were still in Marrickville few years ago before they expanded and moved to a bigger space in Botany.

As described on Precious Plastic’s website, the larger their influence has grown the harder it’s become to keep track of their network. The totally free, open-source nature of their knowledge sharing means they don’t keep records of participants, subscribers or their activities. No one is being granted access, vetted or bartering for licencing.

I’ve often wondered if this is why they still feel like a real underground movement– without big glossy stats for journalists to headline it’s hard to quantify One Army’s relevance. That and they tend to eschew social media (save for Youtube) ‘cause they think it’s gross.

It’s a fascinating movement on so many fronts, proposing an entirely new approach to manufacturing where knowledge and support is shared freely across a global network, rather than gatekept behind impenetrable corporate IP walls, or lost to outsourcing continents and cultures away.

It empowers communities to re-master the means of production, rather than rely on giant corporations and their opaque global supply chains to solve local problems.

It also paints a picture of a radically different socio-industrial structure: one of a diverse, dynamic landscape of micro mills and small-scale players relying on each other and forming coalitions to share resources.

I’ve often wondered whether the same model could be applied to textile waste recovery and manufacture.

MAKE IT SMALL / DO IT ALL

Although Waverley is certainly no micro mill, their approach did have something in common with your local Precious Plastic recycler: managing every step of the production process under the one roof. Full integration.

Fibre (or textile waste) goes in and finished woven blankets come out; a product they themselves proudly sell through their own shopfront, webstore and wholesale stockists. They complete each step of the manufacturing in-house to get from fibre to product– rather than specialising in one part of the process and outsourcing the rest to other appropriately scaled manufacturers (not that this is a particularly viable option in Australia anyway, due to the scarcity of domestic milling).

Although expensive to set up and run at Waverley’s scale, there’s no underestimating how valuable this approach is in enabling a business to swiftly evolve and pivot their product in the face of changing demand or new opportunities, produce at more manageable volumes and avoid waste, and amass expertise laterally to improve operations.

In my mind this is one of Waverley’s greatest strengths, and made me reflect on our own micro mill plans.

The question now being: could we scale things down and house every step of the production process under our own roof. Recovery, spinning and knitting. The focus being on collecting locally sourced post-consumer textile waste, recovering fibre, spinning a yarn and using that yarn to manufacture our own range of knitwear in-house. Small runs, small product drops, ideally even a made-to-order service.

Taking a page out of Precious Plastic’s book, rather than singularly trying to scale up our own mill the focus could be on knowledge-sharing and supporting other individual players and organisations to get a similar micro mill operation rolling in their own neck of the woods.

Scale the approach, not the production volume.

We've already seen some promising developments in the fibre recovery machine space on our European field trip, and with a few key appointments still ahead. I think I'll write my next newsletter on everything we've seen and learnt during this trip– and how it's informed our thinking moving forward. Its been an interesting ride, sitting down with big textile tech players only to pose the rather heretical question: could you make this machine smaller?

Many thanks for reading!

All the best,

Guy